Queensland Legislation

The current whistleblowing legislation is the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2010. It replaced the Whistleblower Protection Act 1994.

Context

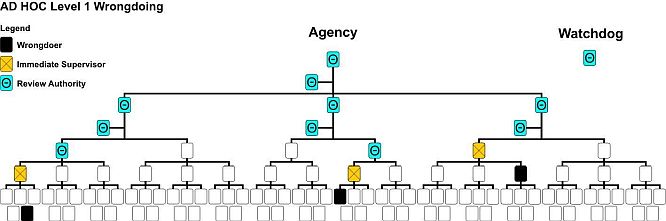

There is a spectrum of corruption situations in which whistleblowing can occur. Two of these are offered in Figures 1 and 2 below. Figure 1 describes the situation where the corruption is ad hoc, local, relatively small in terms of the entity in which the corrupt practices are occurring.

Figure 1: The Profile of Corruption and Integrity where Corruption is ‘Ad hoc’, Local, Small Scale

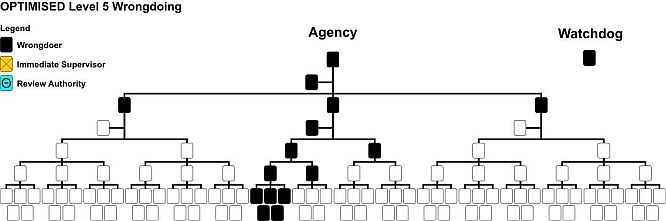

Figure 2 is the other end of the spectrum, where systemic corruption exists within the entity, and the watchdog has been captured and turned away from addressing corrupt practices in the entity.

Figure 2: The Profile of Corruption and Integrity where Corruption is Systemic or ‘Optimised’

The Sword and the Shield policy towards managing corruption, by the protection of whistleblowers and their disclosures, has been designed to support efforts to dismantle systemic corruption.

The legislators in Queensland, however, appear to have assumed, when designing Queensland’s Public Interest Disclosure Act 2010 [PID Act], that corruption is only ad hoc, local and relatively small in scale.

Watchdog authorities in Queensland, such as the Office of Ombudsman and the crime commissions (CJC/QCC/CMC/CCC) appear to share this view.

This was strongly indicated when these watchdogs and others from Federal and other State jurisdictions, served on the Steering Committee for the Whistle While They Work research project – that study assumed that watchdogs were doing a good job (and had not been captured), and that agencies were well intentioned towards whistleblowers, not retaliatory.

These assumptions were made even of the Australian Defence Force, one of the agencies that participated in the Study, which agency has had 21 inquiries into abuse of the military justice system in 21 years.

Analysis of the legislation and of watchdog practices associated with the corruption and the whistleblowing circumstance may thus be best served by two ‘passes’ in logic over these laws, practices and procedures:

The First Pass is done with the assumption that corruption is ad hoc, and that agencies are well intentioned (any retaliation is an error in understanding, say, born of a lack of training, say), and the watchdogs, the Ombudsman’s Office, the crime commission and the like, are actively and independently addressing issues as they arise.

This First Pass and its happy assumption makes sense of, for example, the practice by the crime commission of returning nearly all disclosures against agencies back to those agencies to investigate themselves, because those agencies are well-intentioned and can be trusted with that duty, under the logic of this first pass.

- Provisions in the PID Act specifically allowing ‘reasonable management action’ to be taken against the employment of the whistleblower is itself reasonable, on this first pass, because any such actions taken will be well-intentioned, it is assumed;

- Provisions allowing the entity to decide not to investigate disclosures (on the logic of this first pass) will only be implemented in good faith by a well-intentioned agency – any investigation already conducted would have been carried out reasonably by well-intentioned public officials, according to the first pass assumption;

- Provisions requiring entities to take steps to ensure that individuals involved in the ad hoc corruption do not carry out reprisals against the whistleblower will provide another layer of protection to the whistleblower (on the logic of this first pass). The Ombudsman’s oversight of these steps will ensure quality management of these procedures – yet another layer of protection, it is assumed; and

- The provision allowing the whistleblower to go to the media after six months if the agency does nothing about the ad hoc corruption – (on the logic of this first pass) how powerful a measure this will be in ensuring that the whistleblower’s disclosure is actioned.

The Second Pass through the above matters, then, makes the alternative assumption that the corruption is systemic – the corrupt practice is part of the business plan for the agency or for the industries in the agency’s portfolio of responsibilities … or is a product of a fear-and-favour type politicised corruption in which the agency operates … or a major cover-up of a financially significant fraud or waste, where for these circumstances the watchdog has been drawn into a passive or active complicity.

Consider the case, under the second pass assumption, when the crime commission receives disclosures from a whistleblower, seeking reasonably a review of an alleged cover-up ‘investigation’ by the whistleblower’s agency of disclosed corruption at that agency. In this second pass circumstance, the crime commission’s practice of referring this application for a review back to the allegedly corrupted agency who conducted the first ‘investigation’, is a simple corralling of the whistleblower – every allegation goes back to the agency, from which the procedures allow no escape. In short, the whistleblowers are caught by the agency, whether going away (via a referral to the crime commission) or coming back (via a referral by the crime commission back to the corrupted agency). Also:

- The provisions in the legislation allowing the agency to exercise reasonable management actions to transfer, send for psychological assessment, deploy, make redundant, terminate, etc, (on the logic of this second pass) have been given to the managers of the corrupted agency, who are in a serious conflict of interest situation, and who may have already taken reprisals against earlier whistleblowers;

- Provisions in the PID Act allowing the entity to decide not to investigate disclosures (on the logic of this second pass) have been given to the managers of the corrupted agency who are in a serious conflict of interest situation, and who may have already sustained the systemic corruption by previous cover-ups of disclosures made by earlier whistleblowers;

- The provisions in the PID Act requiring agencies to establish steps to prevent individuals making reprisals against whistleblowers (on the logic of this second pass) are an irrelevancy when it is the systemically corrupted agency that is taking the retaliatory action; and

- The ability to go to the media (on the logic of this second pass) is only available after six months – this is more than enough time to compose adverse performance appraisals, send the whistleblower to the agency’s ‘gunslinger’ psychiatrist for psychological vilification with report, transfer the whistleblower to a lower classification position without much work at a desk half in the corridor, and, if the whistleblower does not resign, make the whistleblower redundant and unceremoniously frog-march him/her to the carpark.

Thus, the tenet upon which the effectiveness of the PID Act depends is whether or not the agency at issue is systemically corrupted or its management are well-intentioned towards whistleblowers. This issue may be resolved by inspection as to whether or not there are whistleblower cases in the records of the entity and by how those cases were resolved.

It is against the stated purpose of government to discourage whistleblowers from submitting their disclosures to government, in all the details of those stories, in QWAG’s view. This discouragement deprives government of demonstrations of agency behaviour towards whistleblowers. Government may be leaving the field to WWTW researchers to ‘inform’ government on this critical determinant, when those researchers may simply have assumed the situation before any survey was initiated.

It has been QWAG’s allegation that there is an accumulation of credible allegations tending to suggest that agencies in the Queensland jurisdiction and their watchdog regulators may have, prior to 2010 (the date of enactment of the PID legislation), and/or may be now, showing indicators that these agencies and watchdogs may have been affected by systemic corruption. The watchdog regulators in Australia promoted an opposite view, using the WWTW reports, by declaring the principal whistleblower cases in Australia to be ‘mythic tales’. In short, by definition, the ombudsman offices and the crime commissions are simply asserting that these whistleblowing narratives are purely fictitious.

If cases of systemic corruption have been demonstrated, and this possibility has not been catered for in the design of legislative provisions and associated practices pertaining to whistleblower disclosures and protection, then those practices and that PID Act may be showing insincerity by the jurisdiction that established and implemented that legislation and those practices. Queensland’s history of:

- the Fitzgerald Inquiry (police);

- the Davies Inquiry (health care);

- the Matthew’s Inquiry (mining);

- the Commissions of Inquiry into dam operations and flooding (engineering)

- the Heiner, Forde and Carmody Inquiries (children in care, justice, protection of official records);

- the Senate Inquiry into Unresolved Whistleblower Cases (reprisals against whistleblower); and

- the Connolly/Ryan Inquiry (watchdog regulators)

… amongst other inquiries, may not justify assumptions that the watchdogs are properly performing their roles. This history of these inquiries may not justify the assumption that agencies are well intentioned towards public interest disclosures and towards those who make such disclosures.

Insincerity has the character of dishonesty, according to the Oxford Dictionary. This is the allegation that may be reasonably made, QWAG submits, about the Public Interest Disclosures Act 2010 (Qld).

Some noteworthy points about the legislation at the time of writing (December 2016) include:

s3(b) asserts that an objective of the legislation was ‘to ensure that public interest disclosures are properly assessed and, when appropriate, properly investigated and dealt with’. That ‘assessment’ step is where, it is alleged, that agencies and watchdog regulators may have intercepted and prevented prima facie allegations going to an investigation and resolution.

s12(1) (d) allows any person, not just a public official, to make disclosures of alleged reprisals, other conditions being met.

S12(1)(a) and s13(c) allow any person to disclose danger to health and safety only of a person with a disability, not to any person. That is a restriction compared to the national legislation which allows any person to disclose a danger to the health and safety of anyone, not just a disabled person.

s30 facilitates the refusal of investigations, such that a purported object of the PID Act is thereby readily avoided. A principal clause for facilitating such an avoidance is s30(1)(a) where any previous ‘appropriate process’ that ‘dealt’ with the disclosure has been effected. This earlier process is usually the agency response, which can be marked by a lack of thoroughness, a lack of fairness, and/or a lack of impartially. The Ombudsman Office has not accepted disclosures until they have been processed by the agency, and the crime commissions have referred disclosures made to those commissions about the agency back to the agency to process. The disclosures are corralled back to the agency who conducted the first process, and then that agency’s first process can be used to deny a proper investigation.

S 30(2) requires that written reasons be given to the whistleblower for decisions made on that first process (and subsequent processes). The abuse of this requirement by agencies, and the acceptance of the breach of this rule by watchdog authorities, is the principal demonstration that the clauses of the PID Act can be simply ignored by the agencies and the watchdogs– either a document giving decisions can be produced or it cannot be produced. Such blatant breaches of the Act render the agency’s first process an inappropriate process, where the PID Act intended that an ‘appropriate process’ be both provided by the agency and enforced by the regulatory watchdogs.

S32(5) places disclosures made to the crime commission outside of the provisions of this PID Act. Disclosures made to the crime commission are managed under the legislation directing the operations of the crime commission.

s34 sets out that a member of Parliament (the Legislative Assembly) has no role in investigating any disclosure made to the member of Parliament, for the purposes of the PID Act. The effect again may be perceived to be corralling any disclosure back to the agencies against whom the public interest disclosure has been made.

s36 Immunity from liability – ‘a person who makes a public interest disclosure is not subject to any civil or criminal liability or any liability arising by way of administrative process, including disciplinary action, for making the disclosure’. This provision, however, may recently have been interpreted by lawyers in various capacities as not extending to disciplinary procedures available through arms of the executive. The immunity against discipline may now have been interpreted to refer only to agency disciplinary proceedings against the employees of that agency. If the employee or person is a member of a profession which needs to be registered under a law of Queensland, and that registration body has powers of discipline over registered professionals, then the immunity s36 may not apply. It may have been proposed and implemented that such disciplinary processes are neither civil nor criminal nor administrative in nature, and thus avoids the protections provided by s36.

s43 provides for vicarious liability of the public sector entity for reprisals made against whistleblowers. This is important. It enables the whistleblower to take civil action against the agency, rather than or as well as against a public servant(s) of modest means. S43(2), however, allows the agency to escape that liability if the agency can prove, ‘on the balance of probabilities, that the public sector entity took reasonable steps to prevent the employee’ from effecting the alleged reprisal. The term, ‘reasonable steps’, like ‘reasonable management action’ (s45) is nowhere defined in the PID Act. As with earlier comments, the structure of this section does not contemplate the systemically corrupt agency where it is the corrupted agency that is reprising the whistleblower. In the latter situation, where contributions to the reprisal may allegedly have come from the supervisor, the HR manager, the agency investigation officer, a general manager and other actors in the agency’s corporate framework, the number of individuals against whom the whistleblower may need to initiate proceedings exposes the whistleblower to very wide legal preparations. Such legal preparations place the whistleblower at considerable risk of financial ruin if the action is lost and costs are incurred for defending counsel for all of the individuals named.

s58 appoints the Office of the Ombudsman as the oversight agency. This fight was fought and lost by QWAG when the Ombudsman Office relieved the Public Service Commission [PSC] of this responsibility. The PSC is also subject to allegations, but the PSC showed signs of effort at integrity that may not have been seen amongst the actions of the Office of the Ombudsman:

- The PSC referred allegations of suspected official misconduct to the crime commissions, something that the Office of the Ombudsman/Office of the Information Commissioner may not to have done allegedly on many occasions, despite the apparent obligation to do so as stated by the crime commission;

- Officers in high positions in the PSC may have been disciplined for alleged improper conduct or behaviour with respect to disclosures and reprisals; and

- Allegations of wrongdoing by the PSC may have been made about the decisions of officers imported into the PSC for particular hearings, officers who had held office in other watchdogs. Complaints against such decisions have been rejected by the PSC.